A week and a bit later, finally posting my most recent piece for local paper Straits Times. This one explores the Digital Silk Road, something I have been looking at a growing amount for this larger RUSI project I have been working on which has a specific cyber and digital strand to it. In other words more on this to come, though more likely from the policy angle than the technical one which I am continually learning about.

Bumps on the Digital Silk Road

Chinese tech giants are superb builders but feared for their prowess and government links. But what if the greater risk lies in these firms themselves?

At the height of the Sino-Indian Himalayan border clash last year, New Delhi suddenly slapped a ban on dozens of Chinese mobile phone apps on security grounds. Most prominent among them was TikTok, the video-sharing app which has taken the world’s teenagers by storm.

The Indian ban came amid a wider wave of pushback against China’s digital and technology companies, led by the United States but taking effect globally in different ways, creating bumps in the building of China’s Digital Silk Road (DSR).

India has always been a major point of interest for Chinese technology firms. With a market size potentially the same as China’s, it offers an opportunity for exponential growth right next door. For TikTok, before the abrupt cut-off, India was its biggest market outside China with some 200 million people on its platform and proof that a Chinese company could take on America’s Big Tech in new markets.

Hardware companies such as Xiaomi and Huawei have long listed India as a major source of growth. In 2018, Huawei announced an “India first” policy and started to establish a growing volume of its manufacturing for the market in the country itself. In 2017, Xiaomi’s sales in India topped US$1 billion (S$1.3 billion), while in the first quarter of this year (notwithstanding political tensions and Covid-19 economic slowdowns) it shipped some 38 million units to Indian customers, accounting for 26 per cent of the smartphone market with an impressive 23 per cent year-on-year growth.

On the software side, Bytedance (TikTok’s parent company) had bet heavily on India prior to the banning, hoping to grow its user base with a local team of around 2,000 staff. Mr Jack Ma’s Alibaba is reported to have invested some US$2 billion in the Indian market since 2015.

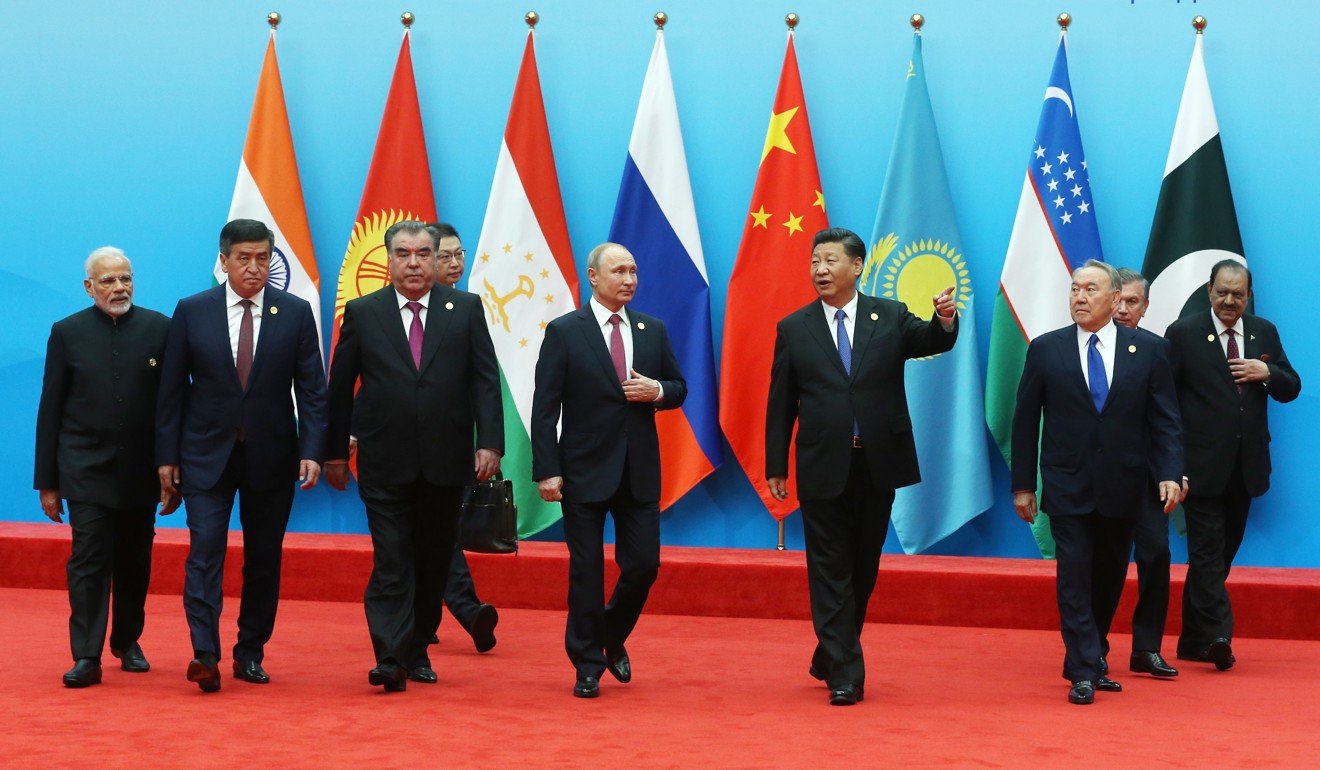

This push into India was the realisation of the vision of the DSR, a concept first laid out by Beijing in a 2015 White Paper. At the time, the DSR was somewhat ignored except in specialist circles as it seemed to be the latest variant of the Silk Road nomenclature in the wake of President Xi Jinping’s 2013 Belt and Road speeches in Astana and Jakarta.

Yet this rather dismissive view belies the potential impact of the expansion of the DSR, which sees China, through its technology firms and state loans, helping recipient countries build their telco networks, e-commerce, mobile payment, smart city and other high-tech infrastructure. Chinese technology companies are paving parts of the world’s digital future.

In the global market, China’s technology firms are more than holding their own. Huawei and Xiaomi phones are affordable and of good quality. Huawei is increasingly the only firm that is manufacturing the infrastructure needed by countries to upgrade their next-generation Internet network. Huawei and ZTE are among the dominant providers of telecoms hardware in the countries surrounding China, while firms like Hikvision or Dahua are offering new technologies at accessible rates.

Chinese online payment applications and fintech are at the cutting edge, while across growing swathes of Asia, Alibaba, Taobao and JD.com online sales platforms are competing robustly against Amazon and other online marketplaces. The easy access to cheap Chinese products makes them very attractive.

An entire sub-economy has emerged of local entrepreneurs in countries such as Kyrgyzstan and Indonesia who create websites in local languages that provide people with access to the Chinese platforms. Across Asia (and more widely), these online middlemen set themselves up as interpreters of Chinese platforms to those who are unfamiliar with the language but want access to the bountiful and cheap products on offer.

In some ways, this is a classic win-win. The countries get affordable technology, investment and access to the Chinese market.

DATA SECURITY CONCERNS

Yet there is another side to it which India was trying to address with its abrupt closure of a whole raft of Chinese apps. Part punitive and part defensive, India’s pushback was amongst the sharpest that China had yet encountered as it paved its Digital Silk Road.

Concerns about privacy, access to data and espionage have increasingly dogged Chinese technology firms. Former president Donald Trump’s White House was aggressive in calling out the dangers of Chinese technology, though his scattershot approach did not always deliver the impact that was intended. Chinese firms and the government have repeatedly denied the accusations levelled against them.

Notwithstanding the Chinese denials, there are areas of concern. In 2017, Huawei removed a Wi-Fi module in a surveillance system sold to police in Lahore when it was discovered by locals. The discovery of the module, which provided an option for remote control that the company had not advertised, caused consternation in Islamabad. Not enough, however, to stop the Huawei chief executive from meeting Prime Minister Imran Khan in 2019 and signing a memorandum of understanding for the company to build a giant cloud data centre in Pakistan. And there have been repeated reports that Chinese-installed technology in the African Union’s headquarters in Addis Ababa have been used to send information back to China.

Separately, TikTok has come under fire in various jurisdictions for censoring data, in part to adhere to Chinese government concerns. In Europe, the Italian government is suing the company for not having adequate protection for children’s data.

The biggest fear at the moment, however, is data collection and access. Driving this is the fear that the Chinese government could in theory demand that any Chinese company hand over whatever data it might have on foreign nationals using its application.

The reality, however, is far more complicated than this. In response to different data protection requirements of the countries they operate in, Chinese tech companies have built data centres around the world to store client information. Singapore, for example, is a particular beneficiary of this trend in Asia, offering a secure location outside China in the heart of Asia. Such centres should be beyond the Chinese government’s reach, though, of course, it can be difficult to monitor this.

But this is not the most interesting aspect of this data collection. Far more important is the volume of information this provides Chinese firms to hone their technical capabilities.

The current rush in new technology is to develop new artificial intelligence tools. In order to train these tools, you need massive amounts of data for them to learn from – something these Chinese behemoths are increasingly gathering in vast volume from around the world and particularly in Asia.

For countries leery of China’s ambitions, this advantage makes the growth of Chinese tech companies not only a potential national security threat, but also an economic threat that could stymie if not kill off rival plans to develop similar tools.

Given all of these concerns, it is not surprising that India decided to block Chinese penetration of its market. For India and others, the worry is not just the DSR burrowing too deeply into their local economies but also the longer-term risk of taking over their digital futures and exposing them to unknown future problems.

VULNERABLE GIANTS

For all that, a less discussed but potentially bigger problem the Digital Silk Road faces comes from within China. The abrupt defenestration of China’s most famous tech entrepreneur, Mr Ma, after he had carried Beijing’s flag for tech growth and innovation around the world, highlighted how vulnerable Chinese private companies really are. Not even China’s biggest tech company, Alibaba, is immune to political censure and punishment.

So far, it appears a chastened Mr Ma is having his wings clipped for challenging China’s domestic lenders too brazenly. His future remains unclear, but the slapdown halted what would have been the world’s largest-ever initial public offering of Alibaba’s payments off-shoot, Ant Financial.

While the scenarios are speculative at this stage, some questions about the relationship between the central government and Chinese tech companies need looking at. What are the implications for contracts or activities run by these companies should they fall foul of the government? What if the Chinese government was to abruptly nationalise or take over parts of Alibaba’s global empire? Countries could find themselves suddenly facing a situation where their entire online payments system was in fact owned by a foreign government.

In other words, the Digital Silk Road’s greatest dangers may not necessarily lie in the possibility of Chinese firms secretly accessing private data or the Chinese state using the infrastructure to hack people around the world, but the political vulnerabilities these firms face back home. If they are less stable than they appear and given the world’s growing reliance on digital economies and infrastructure, the unravelling of key parts of this silk road is a far graver threat than meets the eye.

Raffaello Pantucci is a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies and has a forthcoming book looking at China’s relations with Central Asia.

Image credit: Flickr/Gage Skidmore

Image credit: Flickr/Gage Skidmore