A further piece for the South China Morning Post about what more China could do in Afghanistan. More on this topic over the year as well I think.

Time China met its promises and took leading role in Afghanistan

Beijing needs to move beyond rhetoric and take more concrete action to help and guide the violence-torn nation on its northern borders, writes Raffaello Pantucci

PUBLISHED : Tuesday, 02 January, 2018, 3:03pm

UPDATED : Tuesday, 02 January, 2018, 8:48pm

The year has ended with a number of banner headlines about China’s engagement in Afghanistan.

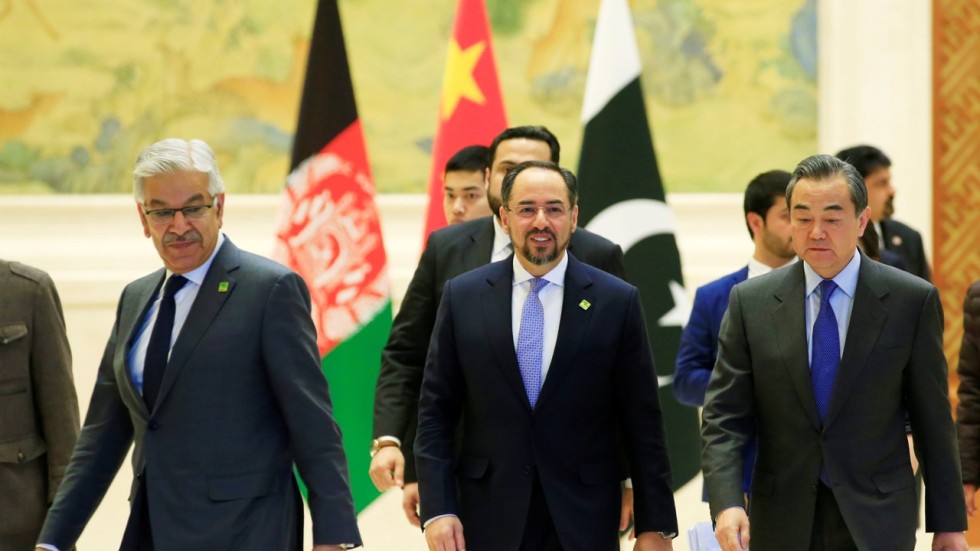

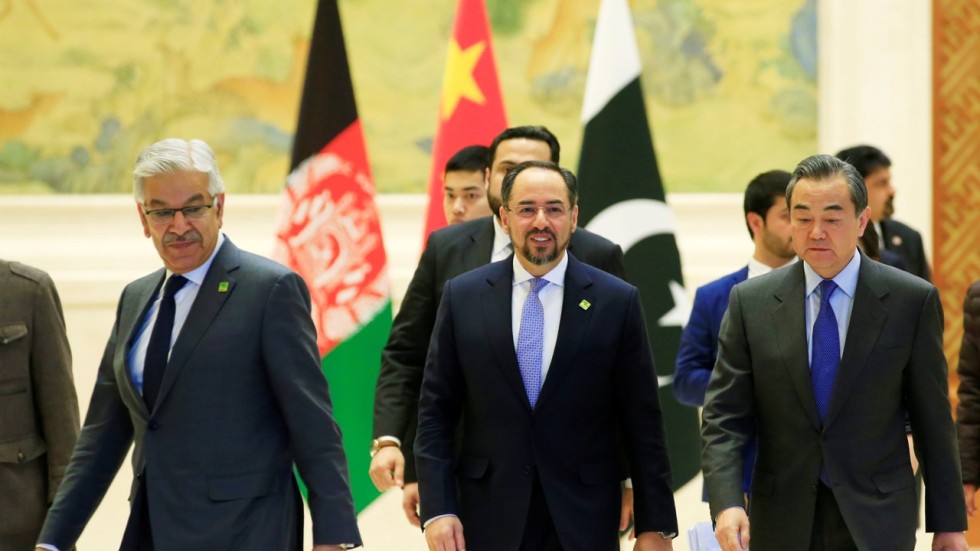

Hosting his Afghan and Pakistani counterparts, Foreign Minister Wang Yi announced China wanted to include Afghanistan in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. At around the same time, one of the messages to emerge from the Afghan defence minister’s visit to Beijing suggested that China was going to invest in a security force in Badakhshan province.

In fact, neither of these announcements is new and while it is good that China is increasing the positive public announcements around its engagement with Kabul, 2018 needs to be the year that China follows through on its rhetoric and takes a greater leadership role in Afghanistan.

The key change in China’s engagement in Afghanistan can be traced back to 2013 when Beijing started to perceive that Washington’s talk of withdrawal was genuine. While the withdrawal was not as complete as was suggested at the time, it showed Beijing that Washington’s commitment to Afghanistan had limits. It also reminded Beijing the glaringly obvious fact that chaos in Afghanistan was something which would have direct ramifications on China. Unlike the US, on another continent, China shares a direct border with Afghanistan.

This started to shape a shift in policy from Beijing. A clearer effort towards engagement was undertaken, even going so far as to undertake joint projects with the United States. China’s political engagement and activity increased and a senior diplomat, Sun Yuxi, was appointed to act as a point of focus for China’s efforts in the country.

And around Afghanistan, growing investment flowed into neighbouring Pakistan and Central Asia as part of Xi Jinping’s keynote foreign policy vision of the Belt and Road international trade and infrastructure initiative. The elevation of these investments under the umbrella of the Belt and Road gave them much greater significance and highlighted the importance of a stable Afghanistan to deliver success in the long-term.

Yet what is surprising in the five years that have followed is the relatively limited volume of activity that has actually taken place or delivered change. China has certainly upped its game in Afghanistan, but it has not yet taken on the game-changing role it could play. Its investments have remained relatively limited and in the case of the largest investment in the country, the copper mine at Mes Aynak, has not moved forwards.

While aid has increased, Afghanistan is a country that needs a sustainable long-term economy, not just aid handouts. Big projects have failed to move forwards and deliver the tax revenues that the country hoped for and Beijing has yet to play a significant role in security terms. On peace talks, China has played a role as honest broker between Afghanistan and Pakistan, but this has so far not brought the necessary actors to the table to foster peace in the country.

Going forwards, China should focus its efforts on a two-pronged effort which focuses on delivering meaningful economic investment into the country and consolidating and leading peace efforts.

On economic investment, Beijing needs to make sure greater investment with local benefits materialises in the country. So far, aid projects have been delivered, alongside some infrastructure investment. Both of these are hugely positive and necessary, but are not providing the sort of transformative economic investment that Afghanistan needs.

Opening up direct train routes and markets is important, but China needs to make it easier for business people in both countries to move back and forth, and for goods to go between the countries. Furthermore, Beijing should incentivise small and medium sized enterprises to develop, something that could be addressed through getting China’s policy banks to extend low interest loans to firms working on or in Afghanistan.

At a larger level, creating a joint investment fund with other international partners to support the construction of infrastructure in Afghanistan would help both encourage Chinese firms to move forwards in this direction, but also help build the necessary physical wiring which will reconnect Afghanistan to its neighbourhood and realise the country’s place in the Belt and Road initiative.

At a more strategic level, Afghanistan needs to develop a bigger tax revenue base. Its natural resource sector is an obvious source that has so far not been tapped as much as it could be, in part as Chinese firms have not lived up to their initial commitments. The government should step in to fix this with companies that have already signed contracts to deliver on them, as well as support others that are exploring opportunities. Copper prices finally appear to be back on an upward trajectory, suggesting that the Mes Aynak project may become more economically interesting again.

The key complaints that companies often find in seeking to invest in Afghanistan are security and corruption. In both contexts, the Chinese government can play a greater role in supporting firms.

China already provides some support to Afghan security forces, but greater central budgetary support would help justify a greater Afghan security role for Chinese projects and investments. On corruption, if Beijing was to work with others (like the West, India and Iran) to ensure the rules of the road in Afghanistan were firmly marked out for their firms that are investing in the country, it could help transform the business environment.

Finally, Beijing should use its growing regional clout to try to bring some order and coherence to the many different regional institutions that have been developed around Afghanistan’s future. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia, the Istanbul or Heart of Asia Process, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation and more have all held varying levels of engagements in Afghanistan. And China itself has created or taken part in a growing constellation of bilateral, trilateral, regional and more forums which focus on Afghanistan.

Kabul needs the attention and support, but a growing problem is a lack of coherence and confusion about which format is actually delivering effective change. It is also stretching Afghanistan’s diplomatic managerial capacity. Were China to try to drive some coherent direction to this range of regional institutions then it might be possible to more effectively marshal the international community. While it will be impossible to ever create a single entity that captures everybody and everything connected with Afghanistan, narrowing down the numbers and focusing efforts would undoubtedly help.

Raffaello Pantucci is director of international security studies at the Royal United Services Institute in London