Another op-ed for the South China Morning Post, on a not dissimilar topic to the last two, focusing on the Belt and Road Initiative and its consequences on the ground. It has gotten a bit of attention on Twitter, and the point is to try to challenge the rather empty policy responses we hear about BRI for the most part.

Beyond this op-edding in the SCMP, have also been delinquent in updating media commentary. Since this was last done, I spoke to the Telegraph about a Pakistani Taliban video, the Independent about the fact that Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s son was killed fighting in Syria, to the Telegraph again about the worrying set of arrests in Germany that included someone who had managed to make Ricin, to Huffington Post about the fact that al Shabaab issued an edict about banning plastic bags, and to the Independent again about ISIS telling its followers to beware of fake social media accounts. Beyond this, The Conversation posted a podcast which included a longer conversation I had had with them about lone actor terrorism as part of the preparation for making this comic strip about the phenomenon.

Why developing countries can’t resist joining China’s massive infrastructure plan

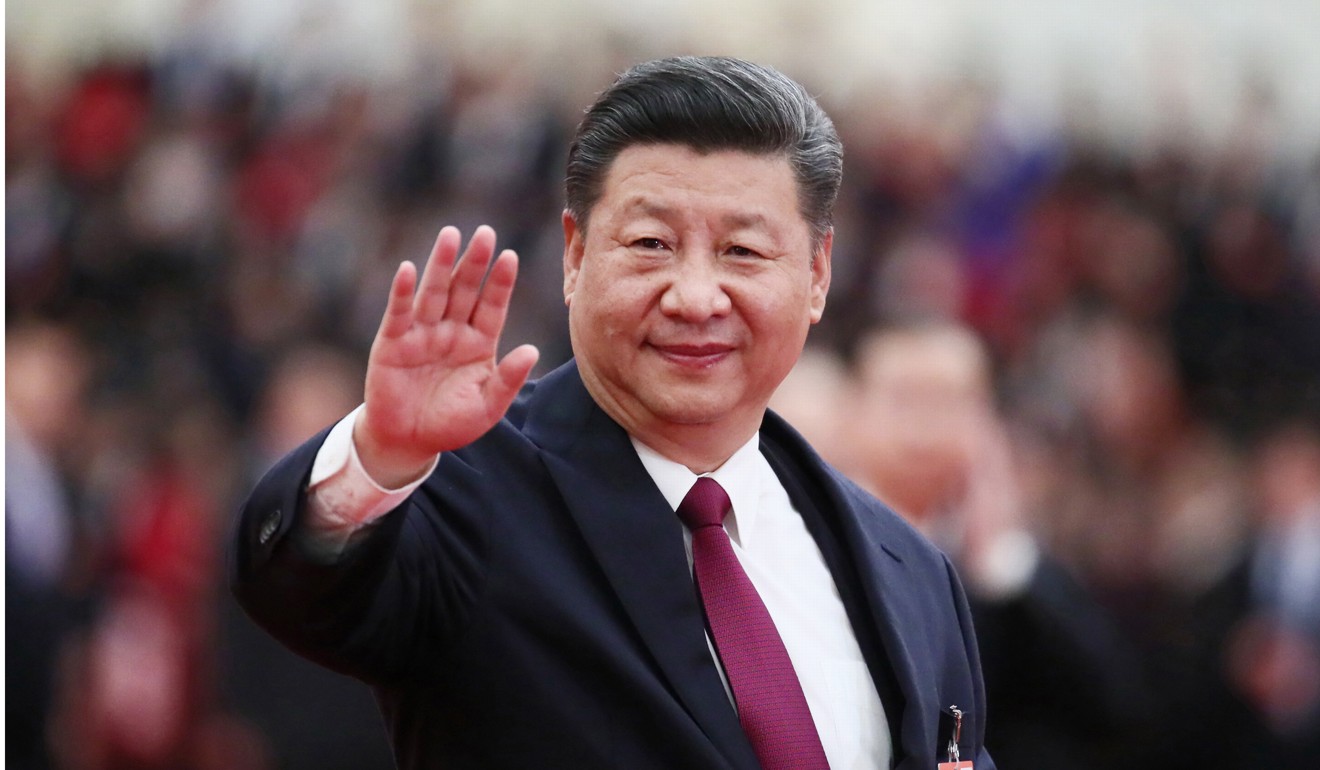

Raffaello Pantucci writes that Beijing’s offer of investment and a connection to a regional ‘balancing force’ is tough to pass up for poor nations with few options

PUBLISHED : Saturday, 07 July, 2018, 10:02pm

UPDATED : Saturday, 07 July, 2018, 10:05pm

6 Jul 2018

There is an understandable trepidation about China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The problem is, there is a tendency to analyse it solely through the lens of China the adversary, forgetting that numerous countries along the way are affected by this foreign policy initiative and their calculation around China has to be very different.

For them, China the adversary is a second-order issue, often trumped by the necessity of seeking either inward investment or a balancer against other regional powers.

If the world wants to find a way of reacting, countering or engaging with the Belt and Road, this is the chief element to bear in mind. Simply rejecting, shouting about or expecting people to reject China’s massive infrastructure plan will have little impact on Beijing’s foreign policy concept.

China has made a dramatic leap in a few generations. From a developing power facing domestic poverty (which still affects substantial parts of the country), Beijing has leapfrogged its way into globe-straddling gianthood, led by a one-party government which talks in dramatic terms about becoming one of the major powers on the planet.

Seen through the lens of this transformation, the Belt and Road Initiative is interpreted as a way for Beijing to restore itself to its rightful place at the centre of the world, with economic corridors emanating from it in every direction.

And there is some truth to this. The impetus behind the Belt and Road is restoring China to its pre-eminent place on the Eurasian continent. But to simply conclude that this effect is the only one, is to reduce the impact for those along the way.

The Belt and Road cuts across vast swathes of underdeveloped Eurasia and beyond, often through countries which have not benefited in the same way from the prosperity in the West. Their governments have not always been able to match China’s breakneck speed of development, and are instead burdened with fundamental domestic issues which impede progress.

Along comes China, offering loans, companies that can deliver projects rapidly and few value judgments about the governance of the countries in question.

There may be some political pressures, but these initially are kept light, and are often focused on matters that are of relatively marginal concern to the countries at hand: recognition of Taiwan, or willingness to back China in the United Nations.

Over time, this dynamic can change. As countries find themselves unable to repay debt, they will accumulate more.

For politicians there is a deep attraction to an outside power that brings jobs, infrastructure and investment. This is an understandable impulse.

If countries are not receiving this investment from elsewhere, or are finding themselves having to fulfil difficult governance requirements to get loans, it is understandable that they will choose the easy option.

Having got themselves into this hole, finding that their predatory lender is leaning with ever greater intensity on them is familiar to anyone who has found themselves taking on more debt than they can handle from the bank.

What is the lesson here? And what is the policy response from the West?

First, there is clearly a need to call out China’s rhetoric of creating a community of shared destiny.

Beijing cannot necessarily be held responsible for bad choices made by other governments, but there can be no doubt that by letting countries take on too heavy loans that ultimately require them to get bailed out by international financial institutions, China is not helping the international order.

Rather, it is taking money from international institutions which help cover debts incurred by countries that use China’s companies to build their infrastructure. This is reducing the volume of money on the planet to help it develop: hardly the action of a globally responsible stakeholder.

Underdeveloped parts of the world need investment. In the absence of other options, it cannot be surprising they welcome China.

But at the same time, China is also merely offering countries an option they choose to take as other offers are absent or unattractive.

This is the perspective the West needs to take.

If other powers want to really counter Belt and Road in the underdeveloped world, they need to think logically about how to do this. Simply telling powers not to take the investment is unlikely to go far.

Offering them alternatives, either bilaterally, in cooperation with other powers or through international financial institutions, is more effective.

At the same time, such choices can sometimes not be an option. China’s economic firepower can be hard to compete against, and in some cases, there are good reasons why countries have been omitted from international financing.

The carrot of investment can be used as an incentive to change behaviour. There is a paternalistic aspect to this approach, but in these contexts, working closely with local authorities to help them develop the capacity to manage Chinese investment is a more productive way forward.

Helping poor countries develop managerial capacity or helping them take advantage of Chinese investment is more likely to have a lasting effect.

The answer to the Belt and Road needs to be a sensible one. Railing against the system when you are not offering anything else is pointless.

China clearly is taking advantage of some poor countries. But these are underdeveloped parts of the world which need investment. And in the absence of other options, it cannot be surprising they welcome China.

This is the crux of understanding how to respond to the Belt and Road. If you want to marshal a more effective response, you need to answer the need on the ground to which it is responding.

Until you do that, you are merely shouting against the storm.

Raffaello Pantucci is director of international security studies at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in London