Longer piece in The Diplomat last month taking a wide ranging look at China’s relationship with the Taliban. Since then there have been even more developments which hopefully should be covered in coming pieces. So keep coming back for more!

Inheriting the Storm: Beijing’s Difficult new Relationship with Kabul

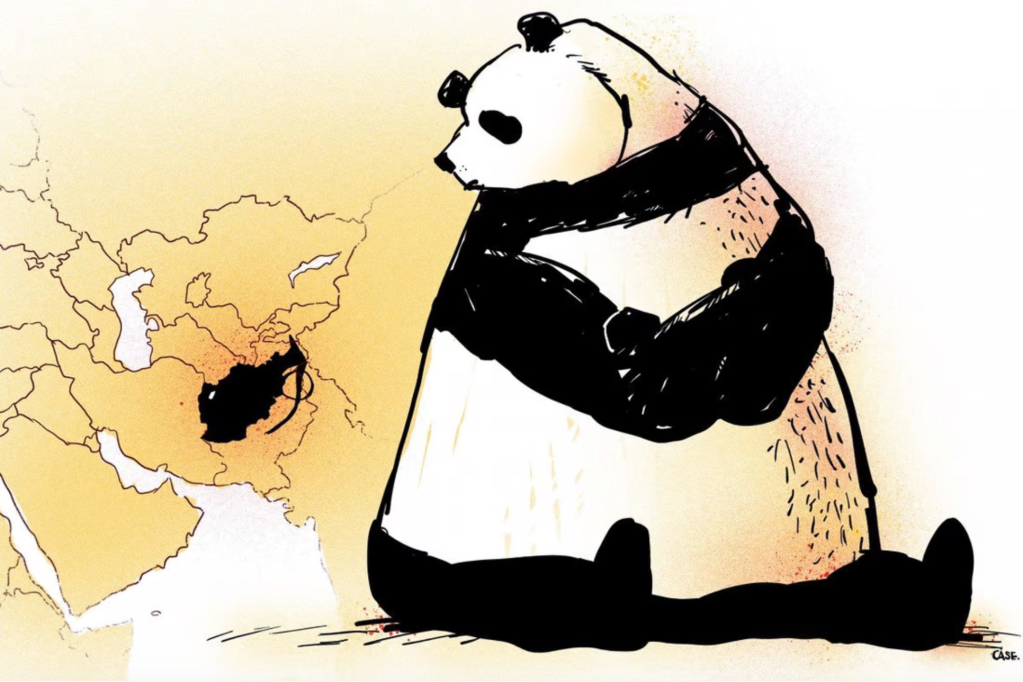

Far from inheriting an opportunity, China finds itself encumbered with an ever-expanding roster of problems in Afghanistan, which it is showing little interest in trying to resolve or own.

The Taliban takeover of Kabul in August 2021 left China with a dilemma. Not only did Beijing now share a border with a country ruled by a group considered a terrorist pariah by much of the world, but China was also the closest strategic ally of the Taliban’s principal supporter in the international arena, Pakistan. As the rest of the world withdrew from Afghanistan, Beijing suddenly found itself in an influential position by default, juggling a number of key relationships without having the shield of U.S. hard power to ultimately hide behind.

In many ways, the image of a sea receding from shore is a useful analogy. While the United States and its allies were present in Afghanistan bolstering the Republic government, a sea washed over Afghanistan that hid a number of issues. As the U.S. and its allies left, this tide retreated, exposing brutal realities on the ground. Among those was the fact that China has no real choice but to engage with Afghanistan given its geographical position and its security concerns on the ground.

Yet this reality has had a remarkably limited effect on China’s actual activity in Afghanistan and the wider region. In many ways, Beijing has sought to continue the relatively limited engagement efforts that were being undertaken prior to the takeover of Kabul by the Taliban. The oft quoted narrative of a Chinese surge was overplayed.

Prior to the collapse of the Republic, Beijing was a partner of the Afghan government, exploring economic opportunities as well as addressing key security concerns. They also explored working with other countries in Afghanistan (like the United States, India, or European powers), and followed through on some limited programming. China was a provider of vaccines and other COVID-19 management tools and had participated in the many different regional engagements that sought to help Afghanistan, including creating specific trilateral formats bringing together Afghan and Pakistani officials. Following the collapse of the Republic government, the level of activity at an official level has stayed similar, though changed to adapt to the new authorities in Kabul.

In security terms, China cooperated closely with the Republic on Uyghur militants Beijing saw gathering in Afghanistan. They are still trying to build this relationship with the Taliban.

The closing months of the Republic were confusing in this regard.The Republic’s National Directorate of Security (NDS) moved definitively against China by detaining a network of Chinese intelligence agents active in the capital in December 2020. Both Beijing and Kabul worked closely together to keep the story out of the public domain, with then-Vice President (and former NDS chief) Amrullah Saleh tasked to manage the relationship by President Ashraf Ghani.

By early 2021, the relationship had been built up again to the point that Saleh was attending events at the Chinese embassy and praising what China was doing in Xinjiang, while at the same time highlighting through social media the links between Uyghur militants and the Taliban (something the U.S. government had sought to break by delisting the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, ETIM, as a terrorist organization in November 2020).

But as the year went on, the relationship between Beijing and Kabul broke down, with the Afghan side refusing to turn over militant Uyghurs it had caught (as Kabul had done previously).Confirmation of this came in the news that when the Taliban swept through, releasing prisoners in Republic custody, a number of Uyghurs prisoners were among those released. Exactly what led to the rupture is unclear, with stories circulating about the proximity of the Republic government to India, unfulfilled information exchange requests, or something financial.

What exactly happened is still unclear. But as the Taliban swept across the country in 2021, China seemed to increasingly pull back from the Republic government and showed itself even more willing to engage with the Taliban. Beijing even hosted top Taliban figure Mullah Baradar and a delegation in Tianjin, where they met with Foreign Minister Wang Yi, in July 2021. Still, Beijing was careful to continue to maintain the appearance of good relations with the Republic. Shortly before the Taliban’s visit, Chinese leaderXi Jinping spoke by telephone with Afghan President Ghani, likely in part to smooth relations. But it was clear that by this point, relations between the Republic and China were in a difficult place.

By late summer of 2021, Beijing had read the runes and concluded that no matter what happened, the Taliban were going to take some degree of power in Kabul, and this mandated establishing closer links. That approach set a path that Beijing was able to take advantage of when the Republic government finally fell and the Taliban took over.

In the wake of the precipitous U.S. and NATO withdrawal, the public discourse around China in Afghanistan went into overdrive. The chaotic nature of the withdrawal fit with a wider narrative –fanned by Beijing (and Moscow, too) – of Western decline. China’s geographical proximity, engagement with the Taliban, as well as longstanding history of announced (if unfulfilled) investments inAfghanistan all fed a narrative of Beijing stepping in to fill a vacuum left by the United States. People saw the reports of vast untapped mineral wealth and assumed the insatiable Chinese industrial machine would be eager to consume it.

Yet in reality these narratives were vastly overblown. China had long been a frustrating partner economically for the Afghan Republic. Deals had been signed, but no progress had been made. Chinese contractors came and worked on infrastructure projects, but little of the money was actually Chinese; rather it was World Bank or other international financial institution projects with the Chinese simply serving as contractors. Trade was underwhelming, and Beijing seemed unwilling to really find ways of tyingAfghanistan into Xi’s connectivity vision, the Belt and Road Initiative. Once the pandemic broke out, China did step in and provide some medical aid, which was welcomed in the beleaguered country, but this was offset by the sudden closure of the Chinese market to Afghanistan.

On the security side, Beijing and the Republic had a fairly easy relationship. The Republic authorities were quite happy to arrest and turn over any Uyghur militants China sought, as they were for the most part fighting for, or allied with, the Taliban. At the same time, they were willing to accept the fact that China maintained a connection to the Taliban, though frustrations did seep through. Reports that the Chinese, at various points, had supplied arms to the Taliban naturally caused tensions, but the Republic government always saw a greater upside in trying to engage withChina economically than become distracted by this frustration, which was not perceived as a strategic issue.

The Republic continually sought to keep China onside. For example, the Republic did not follow the United States in denying the existence of and delisting ETIM, a closing act by the Trump administration to destabilize things with China. Instead, senior Republic officials continued to refer to the group by the name ETIM and highlighted the links between the Taliban and Uyghur militants. They also seemed willing to defend publicly China’s mass detentions and surveillance in Xinjiang, in stark contrast to the narrative Washington was pushing.

The most complicated part of the relationship was Beijing’s ties with Pakistan. Here, Kabul repeatedly hoped that China would use its influence in Islamabad to try and advance concerns they had. Yet, there was little evidence of this happening. While China did establish a trilateral foreign ministerial format between Kabul, Islamabad, and Beijing, as well as use its influence in Islamabad to bring the Taliban and Pakistanis to the table with Kabul at various moments, none of this was able to change the conflict on the ground. And notwithstanding cooperation on counterterrorism questions related to Uyghurs, there was a shadow of paranoia across China’s engagement with the Republic’s security apparatus, thanks to the latter’s deep relationship with the United States.

Afghans were often frustrated by the China-Pakistan EconomicCorridor (CPEC). They pointed out that while China talked about the Belt and Road in Afghanistan, very little was actually forthcoming, in contrast to the billions pumped into Pakistan. Trying to allay this, in 2019, China pushed the idea of encouraging greater cross-border trade between Pakistan and Afghanistan through the establishment of better facilities and refrigeration points for fruits to go back and forth across the border. This fit into a wider pattern of trying to link the CPEC to Afghanistan, an approach that usually found hostility in Islamabad alongside innumerable practical problems on the ground.

The arrival of the Taliban in Kabul changed the dynamic between Kabul and Islamabad (and Beijing), though not necessarily as much as might have been expected. Relations between the Taliban and Islamabad have proven to be as fractious as they were between the Republic and Islamabad. For China, having long cultivated a relationship with the Taliban, it was easy for Beijing to continue operating in Kabul after they took over. The Chinese embassy did not evacuate in the face of the takeover, though they warnedChinese nationals to find ways out of the country or stay in secure locations. Chinese businesspeople in the city reportedly fended for themselves, while the embassy at one point was reduced to calling on Western support to evacuate citizens as their own plans failed.

But once the hump of the takeover was done, China quickly slipped into a strong public support mode, concluding that the Republic was done and Beijing needed to rapidly establish a relationship with the new authorities. Foreign Minister Wang Yi was an active figure on the regional conference circuit, using every opportunity to push for sanctions relief for the new government while his officials regularly taunted Americans over the failure in Afghanistan.

They were also quick to rekindle the formats that Beijing had established between the Republic and Islamabad, as well as try to find ways of engaging with the Taliban through the many regional formats that have developed over the years around the country. The trilateral ministerial engagement was restarted, and Beijing has reportedly also brought together senior intelligence figures from Afghanistan and Pakistan to discuss problems.

On the economic front, they restarted the “pine nut air corridor” that had been established under the Republic. The corridor sought to quickly bring Afghan pine nuts to the Chinese market, and the government helped make sure they were immediately promoted and sold on high-profile online influencer channels. Aid came in to support the ongoing fight against COVID-19. During the winter of2021, the Xinjiang regional government gave just under $50 million in supplies and aid to the authorities in the neighboring Afghan provinces of Badakhshan, Takhar, Kunduz, and Baghlan.

By November 2022, Chinese Ambassador to Afghanistan Wang Yu highlighted how his country had given “300 million RMB in emergency aid to Afghanistan and continued to complete 1 billion RMB in bilateral aid.” He also confirmed that as of December 1, zero tariffs would be levied on 98 percent of products from Afghanistan being sold to China. Afghan carpets were on display at the China International Import Expo (CIIE) this year.

But big ticket deals have moved much slower, if at all. While China National Petroleum Corporation and Metallurgical Group Corp, the two firms responsible for the biggest projects in Afghanistan – an oil concession in the Amu Darya region in the north and the Mes Aynak copper mine in Logar – have re-engaged with the Taliban authorities, there is little evidence they are moving quickly forward. In an apparent demonstration of a total lack of awareness of the nature of the project (or the earlier signed contract), the Taliban authorities in early November announced that the Mes Aynak project would need more electricity. This highlighted a larger problem that Chinese operators find on the ground, which isa counterpart in the Taliban that lacks much expertise to manage large projects.

The economic problems resonate across the border in Pakistan, too. In an attempt to save money, Pakistan took advantage of the low cost of Afghan coal and the fact that Afghan coal miners lack export options and increased its purchases. But once the story got out that Pakistan was taking advantage of Afghanistan’s problems, the authorities in Kabul hiked up the price of coal. This, however, blew back on the Chinese power companies working in Pakistan, which had arrived as part of CPEC and had long purchased cheapAfghan coal. They complained to the Taliban and continue to lobby to get them to lower the prices once again. Chinese coal miner Chinalco has even started to engage with the Taliban to explore opportunities in the country to get a direct Chinese hand into the industry.

Looking beyond the economy, however, China’s biggest concern about the relationship between Pakistan and Afghanistan is the growing militant nexus that sees China as an important adversary. This has been seen most sharply in Pakistan, where there has been a notable expansion of groups targeting Chinese interests. From being mostly targeted by Baloch or Sindhi separatists, Chinese in Pakistan now find themselves under fire from networks linked to the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), as well as rumors of Uyghur militants within the country working with local partners.

The murder of the Karachi University Confucius Institute director by a female suicide bomber dispatched by the Majeed Brigade in April 2022 crossed a new Rubicon as it showed the Baloch groups were broadening out their range of targets from CPEC-specific projects to any Chinese in the country. A number of Chinese nationals evacuated Pakistan afterward.

It seems to be no coincidence that the surge in violence against Chinese nationals happened alongside the Taliban takeover (though it had already been building for some time). At a practical level, the takeover released a vast amount of weaponry left behind by the Afghan National Army and its Western allies, but it also strengthened a number of militant groups, like the TTP or Baloch organizations, that are increasingly targeting Chinese interests in Pakistan and often have bases in Afghanistan.

In Afghanistan, the Islamic State of Khorasan Province (ISKP) has put out far more anti-Chinese propaganda than any other organization. It dispatched a suicide bomber who claimed to be aUyghur against a Shia mosque in Kunduz in October last year. In claiming the attack, ISKP specifically referenced Beijing’s close relationship with the Taliban as a motivating factor.

All of this adds up to a deeply worrying threat picture for China. While previously Beijing could somewhat hide behind others (the United States), it is now seen as the big power in the region, and it is finding itself facing all of the problems that come with that label.

Additionally, China has not been able to establish the same sort of security relationship with the Taliban as it had with the Republic. While China has repeatedly demanded that the Taliban do something about Uyghur militants, thus far all the Taliban seem to have done is move them from one part of the country to another, from Badakhshan to provinces in Afghanistan’s interior. There have been reports that the Haqqani-linked parts of the Taliban government have worked to support Chinese aims, but there are no reports of people being captured and repatriated, as happened routinely under the Republic.

In a demonstration perhaps of how comfortable he was in Afghanistan, Abdul Haq, the leader of the Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP, the name the Uyghur militant group often referred to as ETIM gives itself) released a video of himself talking to a large crowd of followers and their children celebrating Eid 2022 in Afghanistan. As of now, it does not seem as though there is any appetite in the Taliban government to turn over their close allies.

And the reality is that Beijing is not entirely committed either. All of the big economic talk has not resulted in the investment theTaliban desperately want. Rather, there has been a surge of entrepreneurial Chinese businesspeople into Afghanistan, spotting opportunities posed by a nearby country where, broadly stated, violence suddenly diminished and where there were lots of potential mining and other opportunities. Such Chinese entrepreneurs as a group are a hardy bunch. Their risk threshold is much higher than others (witness the challenging parts of Africa where numerous Chinese firms have decided to go). None of what has been seen in Afghanistan seems to be state directed, but rather is pushed by individuals, small companies, and in some cases regional state-owned enterprises. Beijing itself is barely involved, except in allowing permission for individuals to travel and for the potential material to return home.

But even these entrepreneurs find themselves frustrated, with reports that some early investors have already decided it is impossible to do business in Afghanistan and packed up to go home, writing off their large early investments.

The Chinese embassy in Kabul has avoided these negative stories, and instead championed positive ones – like the multi-modal train and truck route that was opened up between Afghanistan and Zhejiang. Home to the massive international trading market at Yiwu, Zhejiang has long been a place where Afghan business people go. Opening up the route was entirely the product of smart Afghans and some folk in Zhejiang, rather than anything coordinated or concocted by Beijing.

This is the reality of the current relationship between China and Afghanistan. While Beijing continues to talk up its positive acts in the country, it has in fact done very little in practical terms. What Chinese activity is taking place on the ground is often driven by private enterprise, and there is a growing level of frustration in Kabul about the slow pace of bigger projects that could have a more substantial impact on the Afghan economy. On the Chinese side, there is frustration about the Taliban’s inability to deliver on outcomes and an awareness that Afghanistan’s problems are already starting to export themselves around the region.

Far from inheriting an opportunity, China finds itself encumbered with an ever expanding roster of problems in Afghanistan which it is showing little interest in trying to resolve. The Taliban remain a frustrating partner, while Pakistan continues to be a source of concern that struggles with security at home while cozying up toChina’s adversary the United States. Never comfortable in an outright leadership role, China finds itself walking a dangerous tightrope in a region where its actual leverage and capability to achieve goals is limited.